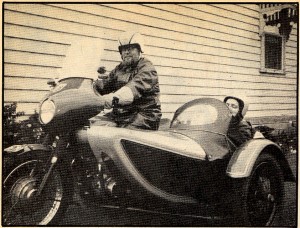

In a recent exchange of e-mails I got to reflecting on how my uncle , Ottar Abrahmsen and my father, Jack Smith taught me as a boy to do various tasks on motorbikes.

Specifically the discussion centred on how to start a Chang Jiang motorcycle. My background is that I have owned and operated a Chang Jiang for over eleven years. Now to quote from my e-mail:

I never use the choke when starting. The coldest I have ever started it would be around 6 degrees Celsius.

- The day your motorbike does not start on the first kick indicates that either your starting regimen was not followed correctly or for some other reason one out of three important factors has gone amiss: (a) there is not sufficient compression, (b) there is not a good strong spark at the precisely correct moment, or (c) there is not a correct mixture of air and fuel in the cylinder.

- He used a punch to put a dot on the throttle mounting and a blade to put a tiny notch in the twistgrip rubber which aligned perfectly when the throttle was totally closed. (I have since done similar markings on every motorbike I have ever owned.)

- Never, ever twist your twistgrip around fully after turning on the petrol tap and before starting the engine or the bike will not start when you kick it. If you want to test throttle movement or adjust the cable, make certain that the petrol tap is turned off before you do so. If you want to test full throttle while riding out on the road, always check your mirror to see that there is not a policeman behind you!

- After checking the bike all over (I won’t put the whole list here, it’s too long!) turn on the petrol tap and tickle the carby: at normal temperatures press the plunger three times and no more; if you will need to wear more than two jackets for the ride, press four times and no more; if there is frost or snow on the ground, tickle four times and hold the palm of your hand halfway across the air inlet opening on the carby while you do the priming kicks. (There was no choke fitted to motorbikes when I was young – the hand over the air intake was your choke.)

- Leave the ignition turned off or the magneto shorted. Prime the engine by kicking it slowly over two or three times to draw some petrol-air mixture into the cylinder(s). This is done with the throttle either fully closed or, on some bikes, with the throttle opened to starting position.

- Turn on the ignition (or open the magneto switch) and check the idiot lights (if any).

- With the throttle one-eighth of an inch open, do one rapid kick on the kickstarter and the bike will start.

- Enjoy a good ride.

- Turn the petrol off and the ignition on.

- Open the throttle flat out.

- Kick like hell until the engine starts.

- Immediately feather the throttle to a fast idle and turn on the petrol tap.

- Enjoy a good ride.

- How to change a tyre;

- how to grind in the valves;

- how to decarbonise an engine;

- how to clean and adjust the carburettor;

- how to recork the clutch;

- how to lubricate the cables;

- how to grease a motorbike;

- or any of a dozen other things.

Looking at that last list, maybe there are some more articles I need to write while I can still remember the details . . .